Scientists have found an extraordinarily rare “hybrid” blood type that, until now, has been identified in three people out of more than half a million tested. Hidden in a massive set of blood samples from a hospital in Thailand, researchers discovered a new version of the B(A) phenotype—an odd kind of type B blood. Before this study, B(A) showed up in about 1 in 180,000 people.

A team at Mahidol University directed by hematologist Janejira Kittivorapart made the finding while trying to figure out why certain patients’ blood tests didn’t turn out as expected.

Their findings, published in Transfusion and Apheresis Science, are an example that the “eight blood types” we often hear about are just on the surface.

What makes this “hybrid” blood type so strange?

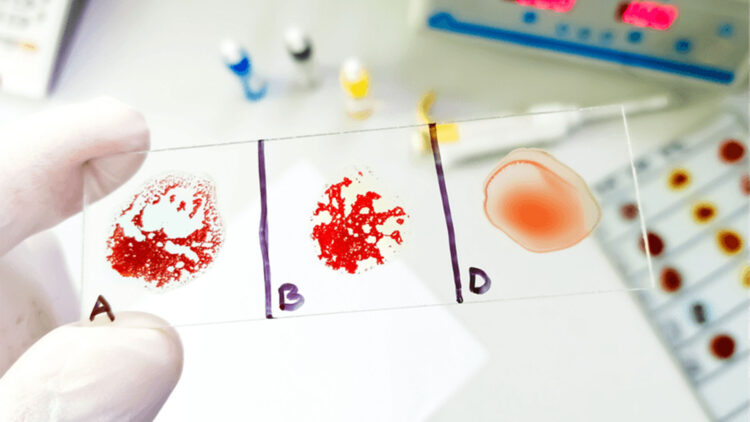

What are the regular blood types? A, B, AB, and O, each positive or negative. Or at least, that’s what most of us think. But these labels are based on small markers called antigens on red blood cells. A and B have different sugar-shaped antigens; AB has both, while O has neither. Your immune system learns to recognize your own antigens as “self” and can fight blood cells that seem too different.

The B(A) phenotype is technically type B, but because of slight alterations in the gene that controls a sugar-adding enzyme, the blood cells show predominantly B antigens, but also a tiny degree of A-like activity.

Blood typing tests look at two things:

- Antigens on red blood cells

- Antibodies floating in the plasma

For an exact result, both have to be identical. Red blood cells and plasma appear to respond differently at times. This is known as an ABO discrepancy, and it can delay medical treatments since doctors need to verify first the patient’s real blood type. With the new B(A) variety, the blood is generally B, but the small amount of A-like antigen activity confuses routine tests, which can make it very challenging on a medical emergency.

How did scientists find just three cases in 544,230 samples?

To see how often strange cases happen, Kittivorapart and her colleagues studied blood tests performed over eight years at Siriraj Hospital in Thailand. In total, they investigated 544,230 samples:

-

285,450 from donors

-

258,780 from patients

Among the patient samples, only 396 (approximately 0.15 percent) showed an ABO disparity. Half came from people who had received stem cell transplants, which can temporarily change blood type, therefore those were excluded. That left 198 patient samples with unexplained inconsistencies. Just one patient had the B(A) phenotype.

Donors had even fewer problems: 74 samples (0.03 percent) with inconsistencies, and only two of those donors had the B(A) phenotype. Altogether, it makes three persons with this rare variant out of almost 550,000 samples.

When researchers looked more closely at their DNA, they identified four mutations in the ABO gene, which regulates the enzyme that adds sugars to blood cells. That combination of mutations has never been reported before. It developed blood that acts like type B, but with that little level of A antigen activity that confuses the conventional testing.

The team ended their paper by writing: “Future studies are required to elucidate the structural and functional consequences of the mutated [enzyme] AB transferase.”

Why do rare blood types like this matter?

In 2024, scientists solved a 50-year enigma concerning a pregnant woman’s blood sample from 1972 and revealed that it represented an entirely new blood group system.

Then, early this year, a team in France published the world’s newest and rarest blood type. Routine tests on a patient from the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe found a blood type called “Gwada-negative”. According to medical biologist Thierry Peyrard from the FrenchBlood Establishment, the patient “is undoubtedly the only known case in the world” and “She is the only person in the world who is compatible with herself.”

These shows how much we still have to understand about something as basic—and important—as blood.